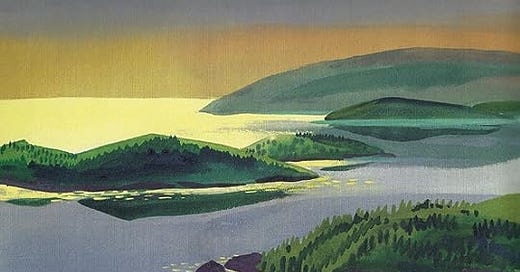

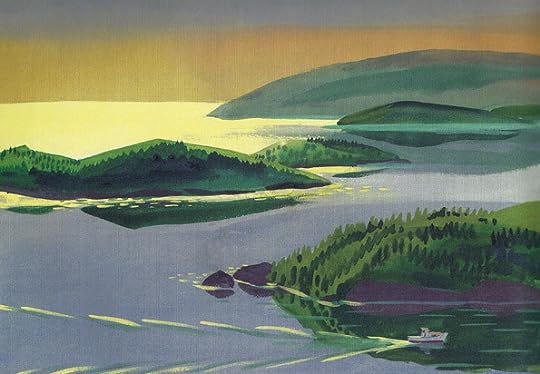

“Out on the islands that poke their rocky shores above the waters of Penobscot Bay, you can watch the time of the world go by, from minute to minute, hour to hour, from day to day, season to season.

You can watch a cloud peep over the Camden Hills, thirty miles away across the bay—see it slowly grow and grow as it comes nearer and nearer; see it darken the hills with its shadow; and then, see it darken, one after the other, Islesboro, Western Island, Pond Island, Hog Island, Spectacle Island, Two Bush Island—darken all the islands in between, until…”

These are the opening lines of Robert McCloskey’s 1958 Caldecott Medal Winner,1 Time of Wonder.

Read them aloud. What do they sound like?

To me, they have the rhythm of Genesis, the cadence of stories meant for oral tradition. These are slow lines. Observant. Philosophical.

They were written for small children who could ‘read’ the beautiful pictures as their adult read the words aloud.

How many children do you know, today, who could be taken with a story that begins this way? How many adults do you know, today, who could be taken with a story that begins this way?

There’s a lot of discussion going on about detoxing from technology and slowing down for October. These are good and much needed discussions. We might start by ridding our lives of noise, even good noise. Some of us may switch to dumb phones; some of us may choose a geographically walkable life; some of us may insist on smartphone-free spaces; some of us might cut out tech every weekend.

But at some point, cutting out the negative has to give way to choosing the positive: choosing to fill our lives with external things that are slower and simpler, too. Are we doing that for our children? Are we doing that for ourselves?

One of the (many) purposes of a picture book is to introduce a child to the world around her. Stories about life which we as adults may find incredibly boring (“June could not find the cat. Where is the cat? There’s the cat! He’s under a chair,”) help the child make sense of her experience.

I have two very vivid memories from my young childhood (age 5 or earlier) tied to books.

The first was about the ocean. Although I have no idea what the title was, I had a picture book which described a day at the beach: the building of sandcastles; the seagulls trying to steal food; sand getting in your teeth when you try to eat sandwiches. Plot-wise, not much happened.

But when I read (or more likely, was read) the line about sand getting in your teeth when you try to eat sandwiches, I remember thinking, “yes! That’s exactly what happens! How do they know?” Growing up on an island with regular beach trips, this was my frequent experience of the world. I was surprised that someone else could have had exactly the same experience.

The second is tied to an illustrated version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous poems for children, in particular one called Bed in Summer, which bemoans the plight of a child:

And does it not seem hard to you,

When all the sky is clear and blue,

And I should like so much to play,

To have to go to bed by day?

“How does he know?” I wondered to myself, as I jealously listened to my older siblings playing neighborhood hide-and-seek. Again, I was struck by how utterly understood I felt by someone I didn’t even know. He had named my feelings, precisely.

While technology gives us access to information, and fast, it does not have the same power to make us feel understood, or the power to help us truly understand the world around us.

When is the last time you watched a cloud peep over the hills, “grow and grow as it goes nearer and nearer,” darkening each patch of land as it drifts?

When is the last time you sat with a child to watch the clouds with him?

There is an entire generation that seems to be having a lot of trouble navigating the world. I don’t mean only that they are slaves to Google Maps, but that they seem to lack a basic understanding of how things work, how people work, what can be reasonably expected, and how to deal with difficulties. Could it be because, from a very young age, they have not had to actually inhabit the world in which they live?

(And are we aging few who remember a slower life any better? A few years ago I gave a talk on technology and life to a group of women, and one came up afterwards waving her phone at me. “I’m 90 years old and I’m completely addicted!” she announced. None of us are exempt.)

Perhaps we, and our children, need to re-learn how to inhabit the world around us.

Perhaps stories can help.

Why not enjoy an October evening reading slow stories by candlelight?

If you aren’t sure where to begin, why not try Time of Wonder by Robert McCloskey or A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson?

(You don’t need to have a child with you as an ‘excuse’ to enjoy these delightful works of literature.)

If you want the joy of incredible illustrations, no words, try anything by Peter Spier or Anno.

If your kids are bit older, or you want a nightly read-aloud by chapter, try Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransom.

Slow down, read aloud, read slowly, and savour. The world might just feel a tiny bit less overwhelming.

The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the American Library Association to the illustrator of the most distinguished book for children. Most of the books with this medal are absolutely gorgeous.

Beautiful, Kerri! (And thanks for the link to my piece on weekend unplugging!) A few weeks ago, Lenore Skenazy of Let Grow linked (in dismay, of course) to a curriculum for teaching children how to watch clouds. Children do NOT have to be taught such things -- it is we adults who forget!!

Oooo, thanks to this lovely post of yours, I have added both Time of Wonder and some of Peter Spier's books to my Thrift Books wish list. :)